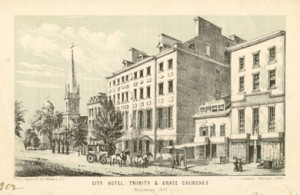

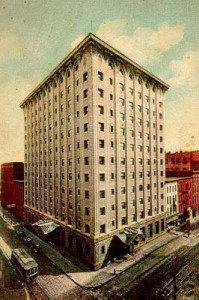

In 1794, the City Hotel opened in New York City and is considered the first building meant to be a hotel.

As much of a princess as I am, when I was growing up I never stayed in hotels. My family always camped. But believe me, I’m making up for it, staying in historic and beautiful hotels all over the world. And whatever hotel I stay in, I try to find out something historical or campy about it.

As it turns out, the history of the modern hotel – which begins in America and dates back to George Washington – is actually quite colorful. Here are some highlights from that history:

• Back in the early days of America as an independent country, traveling was a dirty business. Inns were often little more than drinking taverns with a small number of rooms for travelers. Sharing of beds by strangers was not uncommon, and those beds were often insect ridden. They were places where men abandoned their families for drink and spirited discussions of politics.

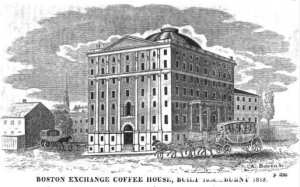

In 1809, the Boston Exchange Coffee House and Hotel was described as an “immense pile of a building.”

• The rudimentary inns and taverns of the day became quite inadequate for the growing country, but within a decade, Americans had built the first hotels – large and elegant structures that had private bedrooms and grand public ballrooms, as well as ones that could provide social, political, and economic advantages and structure to the growing young country.

• In 1794, the City Hotel opened in New York City and is considered the first building meant to be a hotel. It boasted 137 rooms and public spaces such as ballrooms. It became a place to “see and be seen.”

E.M. Statler opened the first business hotel, the Buffalo Statler, in 1908 with the motto of “a bed and a bath for a dollar and a half.”

• In 1809, the Boston Exchange Coffee House and Hotel was described as an “immense pile of a building.” It had a five-story atrium ringed with balconies with each level supported by twenty columns. There were more than 200 rooms, and the whirl of activity within the hotel caused one commenter to say that it had the appearance of a small city. It cost $500,000 and was the largest building in the U.S. at that time. In 1818, a fire, which started in the attic, destroyed the building because the Boston Fire Department did not have a ladder tall enough to extinguish the flames.

• When the Tremont House opened in Boston in 1829, it was the finest hotel in the country. Designed by architect Isaiah Rogers, the four-story, neoclassical building contained 170 rooms, including parlors and dining rooms. It was the first hotel to provide indoor plumbing and running water. There were eight toilets on the ground floor and bathrooms in the basement for bathing. In addition to water pitchers and a washing bowl, free soap was provided in each room. The Tremont House offered French cuisine and, reportedly, was the first hotel to have bellboys.

Topeka’s Harvey House dining room, 1920s. By offering good food served promptly – in sharp contrast to many other early Western eateries – Harvey House enjoyed tremendous success.

• The next generation of hotels was fueled by the developing travel and transportation infrastructure. As steamboats and railroads spurred an increasingly mobile society, the hotel industry expanded. Locomotives needed repairing about every 100 miles and thus needed to stop. There were no sleeping or dining cars until the 1860s, so passengers needed to be let out and have a place to rest.

• E.M. Statler opened the first business hotel, the Buffalo Statler, in 1908 with the motto of “a bed and a bath for a dollar and a half.” It was the first of a chain of hotels designed to provide clean, comfortable and moderately priced rooms – with bathrooms in every room, a first – for the average traveler.

• Our legacy of hospitality leadership spans more than a century, beginning with Fred Harvey, a talented visionary who saw the need for quality hotels and restaurants for weary travelers making their way West. Harvey opened the first of his highly successful Harvey Houses in 1876 in Topeka, Kansas, devising an ingenious telegraph system to notify his restaurants well in advance of train arrivals, making it possible to feed hundreds of passengers in a short period of time. By offering good food served promptly – in sharp contrast to many other early Western eateries – Harvey enjoyed tremendous success. The famous “Harvey Girls” – carefully trained, well-groomed young women who were hired as waitresses – further increased customer traffic.

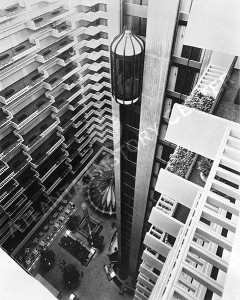

The Hyatt Regency Atlanta opened in 1967 as the world’s first atrium hotel. When it opened, visitors lined up to see it, described by one critic as “a concrete monster.”

• Construction of the Boulder Dam – later named the Hoover Dam – was the catalyst for the development and character of Las Vegas, whose population swelled from around 5,000 citizens to 25,000 in the early 30s. Dam construction workers were men from across the country with no attachment to the area, which created a market for large-scale entertainment. A combination of local Las Vegas business owners, Mormon financiers, and Mafia crime lords helped develop the casinos and showgirl theaters to entertain the workers.

• Architect John Portman’s hotels set a modern, upscale tone. His Hyatt Regency Atlanta opened in 1967 as the world’s first atrium hotel. When it opened, visitors lined up to see it, described by one critic as “a concrete monster.” The top of the hotel features a Jetsons-like flying saucer, and the 23-story atrium created a stir with its innovative use of space. The atrium was the prototype not only for future downtown hotels in the city, but also for a number of hotels throughout the U.S.

Eleanor Schrader is an award winning architectural and interior design historian, professor and consultant who lectures worldwide on the history of architecture, interiors, furniture, and decorative arts. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.