New Book Puts Spotlight on Often Forgotten Artists

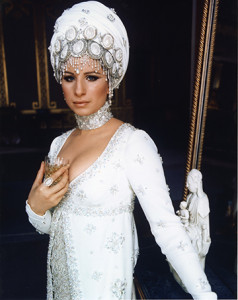

With the Oscars coming up soon – and endless buzz and speculation on winners – a new book puts the spotlight on the relatively hidden lives of Hollywood’s costume designers, from the Silent Film era to now.

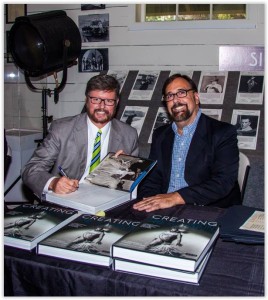

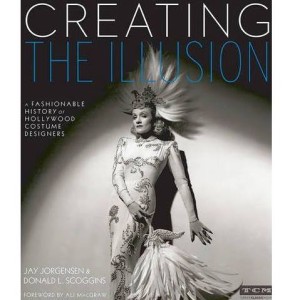

Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers by Jay Jorgensen and Donald L. Scoggins is a gorgeous book with stunning photos and equally compelling stories of more than 50 designers. These designers might not be household names but they nevertheless have had a great impact, not only on film and TV, but also on culture and society. The book contains never-before-revealed details of the lives of many of these designers, as well as mysteries, colorful anecdotes and tragic events.

Jorgensen has had an interest in costume design since the 1990s, when he started collecting sketches and photos of designers’ works. In fact, his first book, Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was published by Running Press in 2010.

Head was a great self-promoter with a long trail of press coverage, but for many other designers, little was known.

“You can find out a lot about couture designers, but there wasn’t much information about the film designers, who I think influenced fashion designers because they saw lots of movies,” Jorgensen said. “It frustrated me.”

And so, he teamed up with co-author Scoggins, and they embarked on a two-plus-year journey to bring to life these artists.

Scoggins is an attorney who searched public records, including passport and Census documents, military records, court transcripts and more. Jorgensen, a photographer by trade, also did research and interviewed people in the industry, designers’ relatives and friends, and others.

Many of the stories came from Jorgensen’s friend and costume designer David Chierichetti, whose 1970s book, Hollywood Costume Design, was a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood costume designers – their family lives; their relationships with stars and moguls; and often, their struggles with addiction or the premature end of their career. Over many years, often over lunch, Chierichetti would tell Jorgensen stories, more and more of which Jorgensen was able to use as the designers died.

“Creating the Illusion” is a gorgeous book with stunning photos and equally compelling stories of more than 50 designers.

The lives of many of the designers featured in the book turned out to be as wild and glamorous as those of the movie stars for whom they designed. In the 1920’s, as prohibition reigned, Paramount designers Howard Greer and Travis Banton caroused Hollywood night spots and lavishly decorated their homes; MGM created an elaborate black, white and gray salon to induce the designer Erté to work at the studio; and Rudolph Valentino and his costume designer wife Natacha Rambova went so far over budget on costumes and props for The Hooded Falcon that the production was canceled.

“In the Golden Age of Hollywood, there was also plenty of tragedy,” Jorgensen said. “Alcoholism plagued the lives of MGM’s Dolly Tree and Irene, RKO’s Edward Stevenson and Warner Brothers’ Orry-Kelly. But that didn’t stop them from creating spectacular designs, along with designers like Jean-Louis, Adrian and Edith Head, who also experienced their own career upheavals.”

As to the images in the book, Jorgensen says, “I wanted to show, not every design, but designs that women today would love to wear, even if they were over-the-top. And I also wanted to show some designs that I really like but aren’t necessarily well known.”

What part of the book did you enjoy writing the most?

Jorgensen: I was intrigued by the abrupt end in 1926 to the career of Clare West, who was the costume designer for D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille and is believed to be the first person credited as a designer in films. It took a lot of detective work, particularly on the part of my co-author Scoggins, but we discovered that she had a rather inglorious end, dying from natural causes in 1961 while living in a trailer park in Ontario. All of West’s siblings and their children had died, but Scoggins found two grandchildren from West’s second marriage. With their help, we learned that West was bi-polar and that it wreaked havoc in both her professional and personal lives. Because of what we learned from her grandchildren, it gave her story more humanity than any other story. I was happy to bring that out.

Scoggins: The litigation over Columbia designer Robert Kalloch’s estate following his death fascinated me, primarily because of its surprisingly progressive resolution. Kalloch died the morning of October 19, 1947, and his longtime boyfriend, Joseph DeMarais, who worked as his secretary, died a few hours later. In his will, Kalloch left everything to DeMarais. Because DeMarais survived Kalloch by a few hours, his estate was poised to receive all of Kalloch’s property. So DeMarais’ working class relatives would end up receiving Kalloch’s estate. Kalloch’s well-to-do Upper Eastside family sued to invalidate his will – alleging his relationship with DeMarais was “unnatural – and that his estate should instead pass to them. The legal battle raged for years, but the press refused to cover it because a gay relationship was considered obscene. In a move that was way ahead of its time, Los Angeles County Counsel defended the men’s relationship and Kalloch’s will, which was ultimately upheld. Ironically, had this happened in today’s marriage equality era, the estates would have been divided equally between the families.

Which designs and designers do you admire the most?

Jorgensen: My favorite costume is Paul Zastupnevich’s gown for Stella Stevens in the 1972 film The Poseidon Adventure. It worked so perfectly for Stella’s character as a retired hooker. I also admire Travis Banton, who worked for Paramount in the 1930s and is known for his costumes for Marlene Dietrich. The silhouettes were so beautiful.

Scoggins: From elegant gowns to tailored business suits, Irene Lentz knew how to design clothes to flatter the female figure better than any other designer. She honed that skill designing for L.A.’s wealthy women at her salon in the legendary Bullocks-Wilshire department store. Her stunning, all-white wardrobe for Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice inspired fashion trends that still find expression today.

What are a couple of your favorite anecdotes from the book?

Jorgensen: Everyone knows something about the tragic life of Judy Garland, who was beset by incredible insecurity and haunted by demons. But what is not so well known is that Garland confided in designer Walter Plunkett, who talked her off a ledge during the filming of Summer Stock (1950).

I also love the “feathers” story from the shoot of the famous Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dance “Cheek to Cheek” from Top Hat (1935). Rogers had asked that ostrich feathers be included in her costume, but they kept falling off and floating into the air or landing on Astaire’s tuxedo, infuriating him. As it turned out, the camera did not pick up the feathers and Astaire finally acquiesced to using the costume – though the famous scene took many takes.

Scoggins: Nothing illustrates Marilyn Monroe’s flirtatious personality and Jean Louis’ classy demeanor better than the story of their first meeting. Marilyn invited the designer to her home, where her assistant greeted him with caviar and champagne. Marilyn made her grand entrance wearing nothing but a fur coat and heels. Dropping the mink to the floor, she told Jean Louis, “I thought you would want to see what you have to work with.” Ever the gentleman, Jean Louis fixed his gaze squarely into Marilyn’s eyes, and said, “I see you wearing hats. Lots and lots of hats.”

There is much talk currently about the underrepresentation of ethnic minorities in Hollywood. Is this an issue for costume designers?

Well, there have really been only three or so prominent African American designers. And one of them, Bernard Johnson, was hired only to do black films. For an industry that seems so progressive, it has a long way to go.

Two of the mysteries you explore in the book were the mysterious drowning death of Universal costume designer Vera West in 1947 and the odd deaths of Columbia costume designer Robert Kalloch and his partner Joseph DeMarais on the same day in 1947. Tell us more.

I didn’t solve the mystery of Vera West, though I have suspicions about the role her husband might have played in it. As to the Kalloch-DeMarais deaths, turns out it was just a bizarre coincidence they happened to die on the same day. Kalloch died in the morning of a heart attack, DeMarais in the afternoon succumbed to alcohol-related liver disease.

What’s next for you?

Jorgensen: I think a second volume. I easily have enough material and images for one.

Scoggins: We had to eliminate nearly two dozen designers from the initial draft of Creating the Illusion to accommodate our space limitation. Just yesterday, a recently retired designer accepted my request for an interview. I think we have enough stories for two more volumes.

(Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers by Jay Jorgensen and Donald L. Scoggins is published by Running Press (2015) and has 415 pages and features more than 400 black-and-white and color photographs. $65.00, cloth. Available on Amazon, Turner Classic Movies, and other online sites and in bookstores such as Barnes & Noble, Vroman’s, and Book Soup.)