March is Women’s History Month, so there is no better time to pay tribute to the ladies who led the way in interior design. You might think that women have always dominated interior design, but trust me, females making their mark in the field around the turn of the 20th century were true pioneers.

Candace Wheeler (1827-1923), often credited as the “Mother of Interior Design,” was an American feminist who believed that women should be able to make a living in art and design. She felt this was particularly so for the thousands of Civil War widows who needed to be able to support their families. For that era, hers was a radical position to take.

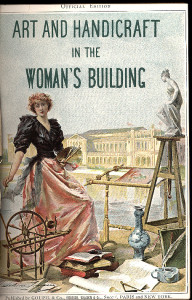

Wheeler did the interior design for the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago

A textile as well as interior designer, she was instrumental in developing art courses for women in a number of major American cities and was considered a national authority on home decoration. She is also noted for designing the interior of the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. (Interestingly, the building itself was designed by one of the few women architects in 19th-century America, Sophia Hayden, who graduated from MIT. As her first project, she designed the 80,000-square-foot, two-story building. A young woman, Hayden evidently suffered some kind of breakdown by the end of the project and never again designed a building.)

Another early pioneer was Elsie de Wolfe (1859-1950), an American actress and interior decorator who set the stage for a completely different design sensibility. She radically changed Victorian interiors – with their clutter and use of heavy velvets and materials – in favor of pale-colored walls, delicate trellises and the more graceful Louis XV and XVI furniture.

Later, when she moved to France (where she purchased the Petit Trianon home on the outskirts of Versailles), she made her mark with the use of Asian decorative arts, animal prints and comfortable chaises longues.

What launched her career was the 1905 commission for the interior design of The Colony Club in New York, designed by her friend, the architect Stanford White. The building, located at 120 Madison Avenue, (near 30th Street), became the premier women’s social club. It opened in 1907, and its interiors garnered her recognition almost over night. Instead of the heavy, masculine style of the day, she used light fabric window coverings, painted the walls with pale colors, tiled the floors, and added wicker chairs.

The New Yorker magazine has said that de Wolfe invented interior design as a profession.

And then there was the “British Elsie de Wolfe,” Syrie Maugham (1879-1955), wife of W. Somerset Maugham. (Maugham and de Wolfe would become rivals of a sort.)

Maugham became famous for her all-white rooms – white couches, white rugs, white furniture, etc. Her elegant Art Deco whiteness was radical for its time, but it established her reputation.

She started her own interior decorating business at the age of 42 in London in 1922, and as her reputation grew, so did her business. She later opened shops in New York and Chicago, and designed homes in Palm Springs, California and cities all over U.S.

One of her better-known interior designs was done for theatre legends Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne at their Ten Chimneys estate in Wisconsin, which is now open to the public as a world-class house museum and national resource for theatre, arts, and arts education.

These three women created fresh, new, exquisite interiors – and led the way for generations of women to follow in their footsteps. For that, we thank them.