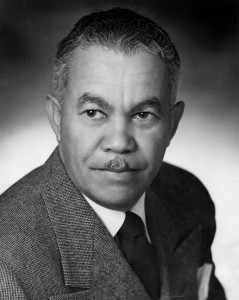

Paul R. Williams.

So much has been written about the incredible life and career of pioneering African American architect Paul R. Williams that it’s difficult to add much new to the story.

Nevertheless, given that it’s Black History Month – and that the 120th anniversary of Williams’ birth was just marked on Feb. 18 – it seems only fitting to highlight some of his achievements.

A native Angeleno who was born in 1894 and was orphaned by the age of 4, Williams was raised by foster parents in a diverse neighborhood in which he learned to be resourceful. Los Angeles was segregated for most of the first half of the 20th century – both in housing and professional opportunities. Indeed, one high school counselor told Williams, “Who ever heard of a Negro being an architect?”

Yet, Williams would go on to a career that spanned almost 60 years in which he designed, built, or remodeled more than 3,000 projects all over the world, from Canada to Jamaica, Hawaii to Liberia, New York to Colombia, and most famously his hometown of Los Angeles.

One of my favorites is Williams’ Saks Fifth Avenue, Beverly Hills, 1939. (Photo Courtesy of Karen Hudson.)

Early in his career, he was keenly aware of his race when trying to win over new clients. He wrote, “During the early years of my practice, prospective home builders frequently came into my office without being aware of my color. Perhaps they had merely been attracted by the sign on my door. Perhaps they had seen somewhere a house of my design, liked it, and inquired until they discovered the name of the architect. Most of them were obviously serious in their intention to build. Yet, in the moment that they met me and discovered they were dealing with a Negro, I could see many of them ‘freeze.’ Their interest in discussing plans waned instantly and their one remaining concern was to discover a convenient exit without hurting my feelings.”

So he developed the ability to draw upside down. In those days, potential clients would have not sat next to him – they sat across the table. As Williams sat on the opposite side of the table making suggestions and sketching out their joint vision, wary customers were quickly engrossed in the visualization of their dream homes

This Spanish Colonial by Paul R. Williams blends with its environment. Windows are strategically placed to capture views of the Hollywood Hills.

Eventually he would design homes for some of the biggest Hollywood stars, including Tyrone Power, William Holden, Barbara Stanwyck, Zsa Zsa Gabor and Ronald Reagan. In addition to the design of private homes, his work included hotels, department stores, schools, airports, and public housing.

Yet for all the beautiful homes that he designed, he couldn’t call any of them one of his own.

“As I sketched plans for large country homes in the most beautiful places in the world, sometimes I dreamed of living there,” he wrote. “I could afford such a home, but each evening, I returned to my small home in a restricted area of Los Angeles where Negroes were allowed to live.

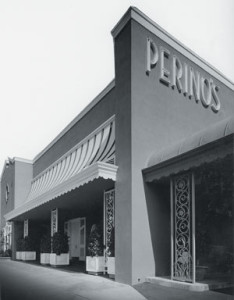

Another of my favorites is Perino’s Restaurant Los Angeles (1949) with the signature sheet-metal awning. (Photo Courtesy of Karen Hudson.)

By mid-century he was employing 60 people in an office on Wilshire Boulevard. Williams was thrilled to have so many opportunities to design mansions, but he was always concerned about affordable housing for those less fortunate. Williams gave his attention to the problem of public housing, a front-burner issue during the Depression and in the post-World War II years, and in 1933 was appointed to the city’s first Housing Commission.

After World War II, architecture shifted away from the romantic revival styles and towards a spare, more economical, utilitarian ideal. In 1945, responding to the post-war housing shortage, he published a book called “The Small Home of Tomorrow” and followed it with “New Homes for Today” in 1946. The books advocated open plans, flatter roofs, and a minimum of ornament. A number of low-budget designs were demonstrated, including the Richard Neutra home. Williams and Neutra had collaborated on a government housing project a few years earlier.

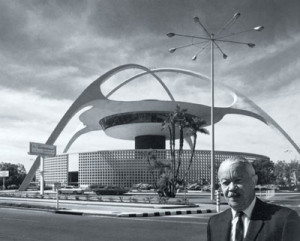

LAX theme building (1960s). Williams designed this futuristic landmark with architects William Pereira & Charles Luckman. (Photo Courtesy of Karen Hudson.)

Williams is thus known for a variety of styles – from the Jetsons-like Theme Building at LAX to elegant mansions. For me, Williams’ work is admirable because of its grace and elegance. In addition, he had a true understanding of what architecture should be. He was not only a gentleman, from all accounts I’ve read, but worked tirelessly for his community and the betterment of architecture and the human environment.

One of my favorite interiors is his Saks Fifth Avenue interior of 1939. (Scroll down). On the same website, you can see another of my favorites, Perino’s, which unfortunately is now gone. I also admire his imprimatur at the famed Beverly Hills Hotel, both in the Fountain Coffee Shop and the signage.

I am always awed by someone who overcomes insurmountable odds, and Paul Williams certainly did that.